Tanner’s Thoughts

In October 2011, I found myself alone, hungry, and in Guadalajara Mexico. It was my first time here. In fact, this was my first international trip ever.

Standing in front of the door, my stomach grumbles again. I haven’t eaten all day. A few months earlier, also for the first time ever, I earned a spot on the US National Team for Paralympic track and field. I’m in Guadalajara to represent the US at my first major international competition; the 2011 ParaPan American Games.

On the way to my room in the athlete village, the person escorting me mentioned how the dining hall is on our left, and if I’d like to eat something, all I’d need to do to get back is follow the cracks along the side of the driveways.

As we shift over to the edge of the street, my white cane falls into one such crack. Swinging my cane left and right, I feel a few deep grooves in the pavement. They remind me of the lined grooves on the edges of a highway. You know, those grooves etched deep in the highway designed to wake you up if your drifting off the road?

This is an ingenious idea. What a fantastic means of enabling someone like myself who’s blind to independently navigate and travel areas they are unfamiliar with. I imagine this awesome physical accessibility feature is rather inexpensive to install and would provide immediate benefit to all white cane users traveling. And if you have any experience in the world of construction, you know about diamond blades.

While reading a recently published article about smart paint being used by the Ohio School for the Blind, I was reminded about my experience at the athlete village in Guadalajara.

As you’ll find out in the article below, this interesting smart paint synchronizes with a detection device that is added to the bottom of a white cane. When a white cane travels across the smart paint, a special vibration is sent up the cane the user can feel, indicating to the white cane user where they are respective to the white paint; just like the grooves on the side of the highway, or at the athlete village in Guadalajara.

Unfortunately, you need a “smart cane” to be able to detect the smart paint, which is facilitated by a technological device attached to the end of your white cane, and it would only work in areas in which the smart paint is installed. How reliable is that? Is it waterproof or resistant? Is it durable? When you see the scratches in my cane from it flying into hard things, you’ll know why I’m asking.

If you’re not a cane user, transitioning from marble to tile or to brick from pavement and from the sidewalk to the street can be felt by a white cane user. It’s all in the vibration. And one of the most violently vibrating surfaces is the street. So how heavy is this smart device? When there’s a relatively heavy object at the end of a 60 to 70-inch cane you are swinging around constantly, how big will your forearms get? Or really, how sore will they get.

The main idea behind the smart paint and vibrating canes is for people who use white canes to know if they’re at the edge of a cross walk when crossing the street. And as someone who’s totally blind, it can be significantly difficult to walk in a straight line. Sounds simple, but throw on a blind fold, walk 100 feet and let me know if you ended up where you intended.

While I personally believe the grooves in pavement would be a better physical accessibility option over the smart paint, I concurrently believe the smart paint could be better used in other environments, such as indoors at schools, workplaces or government buildings.

This seems like a much “smarter” way to enable the blind and visually impaired white cane users to navigate and travel independently. Especially more attractive since one could possibly snap on the vibration device for use at work, at a restaurant, or department store rather than having it weighing down canes everywhere.

While I’m all about using technology to make our lives simpler, easier, and definitely more accessible, why not take an accessibility tip from our friends in Mexico? Put lines of grooves on the edge of crosswalks to independently guide the blind and visually impaired across streets safely.

Original Article

By Anna Ripken: ripken.2@osu.edu

October 22, 2018

Smart paint and smarter pedestrians: The Ohio State School for the Blind is implementing a paint invention that allows the visually impaired to cross streets more safely.

“Smart paint” is being applied to the edges of crosswalks and is made with elements that cause “smart canes,” a walking cane used by the visually impaired, to vibrate when it comes in contact with the paint on the sidewalk. The vibration from the cane allows the pedestrian to remain inside the crosswalk lines while crossing the street, so they don’t veer into traffic.

“What we’re trying to do is provide a system that’s much more granular and much more accurate and much safer for the user,” said John Lannutti, professor of materials science engineering. “That’s essentially smart paint really interacting with them over the long term. Right now, we’re in the testing stages.”

Mary Ball-Swartwout, orientation and mobility specialist at the School for the Blind, said in a statement that the school and its students are excited to give feedback on the products, as input is not often received from those with disabilities who end up being the users of items geared toward that population.

“The students love it,” Lannutti said. “They really think it’s neat. They just get very excited because the cane is telling them something and it normally doesn’t do anything.”

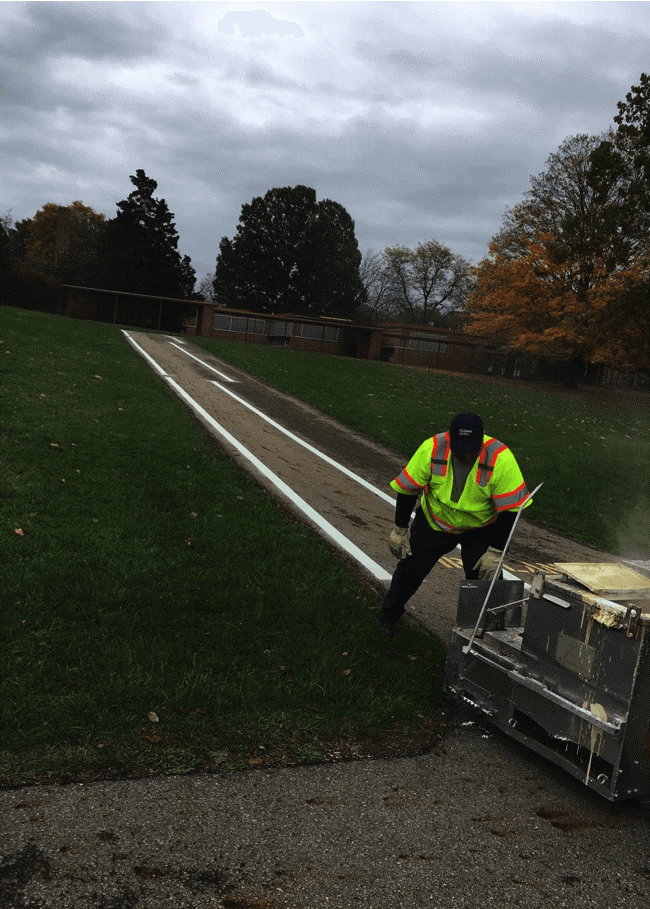

Figure 1: Smart paint was installed at various locations on the School for the Blind campus, so students can interact with the feedback from the cane sensor. Credit: Courtesy of John Lannutti

Lannutti, who is leading a team on this project, also has plans for smart paint to further assist pedestrians with GPS. For example, a GPS app that interacts with smart paint at various locations could help notify pedestrians when they’ve arrived at a bus stop.

“There’s some presets in place to say, ‘OK, this smart piece of smart paint is located at this location.’ They interact with the database that’s on your phone, and it said it arrived at this destination,” Lannutti said. “So, that’s the general concept is that there’ll be previous establishment of where the smart paint locations are.”

Lannutti has been working with Intelligent Materials, Crown Technologies and the city of Columbus on the project.

Intelligent Materials is responsible for manufacturing the additive that makes the paint “smart” and is working on a smart cane sensor that can attach to any cane. Crown Technologies is responsible for actually adding the element to the paint.

“The city has been fantastic, and they are very interested in these types of technologies,” Lannutti said. “And of course, they put the paint down. They showed up with a fleet of trucks and a bunch of guys and they put on this thermoplastic paint for us.”

Lannutti said the cost of the smart paint is 20 percent more than regular road paint, so it is considered an affordable option when it comes to implementing the smart paint in more locations.

The impact of smart paint is spreading to states such as Delaware and Florida, while testing has continued on the School for the Blind campus. Students have been testing out the smart cane technology on the crosswalks.

Read the original article on The Lantern

Fair Use Notice:

In accordance with section 107 of the US Copyright Law, My Blind Spot provides reformatted copyrighted articles – or portions of articles – found on other websites to ensure they comply with regulations governing authentic inclusion and digital equity for people with a disability. The reformatting of these digitally inaccessible copyrighted materials constitutes Fair Use of the same in accordance with the law. Reformatting the articles shared to our membership may not have the full consent of the copyright owner, but My Blind Spot is exercising the disability community’s right to accessible, usable and functional digitized communications and information. This approach not only serves to inform and educate the disability community but serves to educate organizations distributing digitized communications and information about the regulations governing digital equity and authentic inclusion for all people. My Blind Spot advocates for the implementation of accessibility regulations, standards and guidelines, consistently applied when designing and developing digitized publications, articles and communications. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, My Blind Spot in its capacity as a formal nonprofit, believes the distribution of such materials is within the parameters of the law for educational purposes devoid of profitability. Use of any copyrighted materials found on the MyBlindSpot.org website for any other purpose which goes beyond Fair Use guidelines, requires authorization and permission from the copyright owner.

#FairUse

#AccessAbility