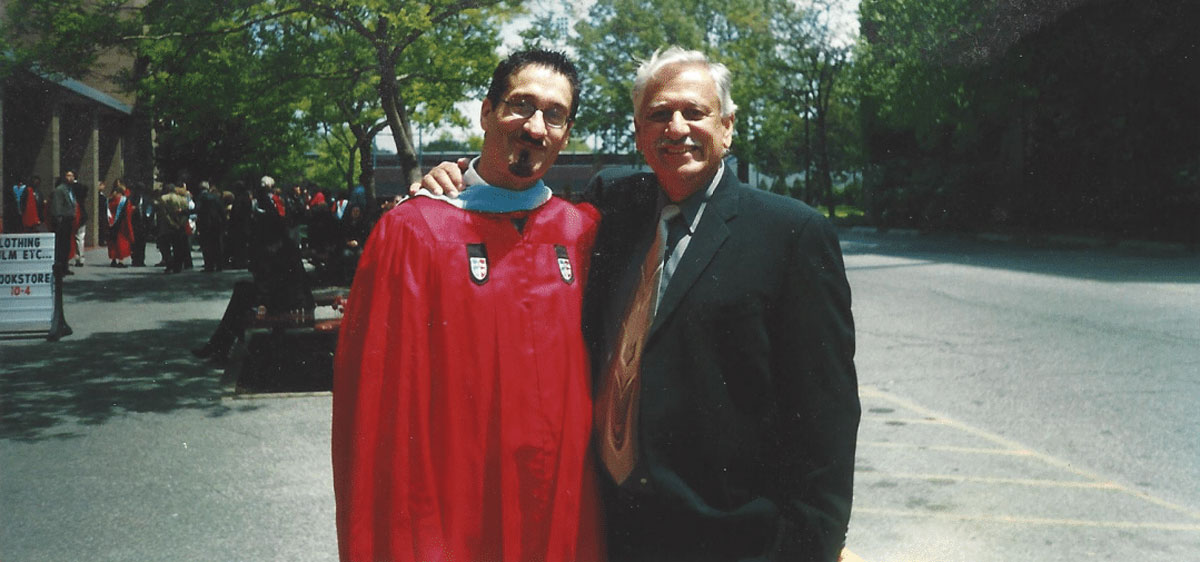

By Albert J. Rizzi, M.Ed.

About two and a half months ago, my father, Umberto “Al” Rizzi, died unexpectedly. My family and I are still reeling from the loss.

He was a husband and best friend to my mother, Iris, for over 59 years. He was a sailor in the Navy and a police officer with the Nassau County Police Department for 26 years. He was a father, grandfather, and friend to many.

Yes, he was all these things, but he proved to be so much more to me when he and my mother rallied around me while I fought for my life in late 2005 and early 2006.

Many know my story by now. How I came to be blind and the life-threatening illness I endured to become the man I am today, a man who also happens to be blind. What my doctors and I thought was my usual sinus infection was something much more sinister: an almost always lethal form of fungal meningitis. I went into a coma.

He and my mother stood by my side, praying and urging me to live. Immediately after moving past what I can only describe as a death spiral, replete with clergy wanting to read last rights, my father provided a dose of fatherly advice. A day or two after learning that I would live and when I needed it most, he kicked me in my ass and made sure that I knew that he and my mother expected me to rise like a phoenix from the ashes that I thought my life had become.

One day, one of my doctors told me that I was lucky to be alive and that there was a 90% chance I would be blind for the rest of my life. You can imagine how something like that might hit a person. I became stoic and contemplative. I held on to the hope that there was a 10% chance things might improve.

A day prior to getting that diagnosis, I had finally been able to hold down food for the first time, and much to my mother’s chagrin, it was a McDonald’s double cheeseburger and not any of her home cooking.

So, dealing with the thought of never being able to see again, I tried to be upbeat and hopeful and was looking forward to eating lunch. It was supposed to be Chicken Caesar Salad. Instead of enjoying that, the person delivering the food that day had a peanut butter and jelly sandwich for me. To say I was disappointed is an understatement. But not getting that salad that I was looking forward to eating became the catalyst to unleashing a cascade of emotions and anger directed at the poor unsuspecting woman who stood before me. F-bombs were dropped, and plates were overturned and tossed about the same time my dad and mom walked in.

In retrospect, I was clearly in the beginning stages of grief, something I had never truly had to deal with. After witnessing this outburst of anger and vulgarity, my father swiftly cleared the room. Without hesitating, he quickly and adeptly administered a dose of tough love under the guise of “fatherly advice.” He told me that it sucked to be me at that moment.

He shared how he and my mother prayed for me, something I do not recall ever hearing either of them doing while my brother and I were growing up. He shared that when they learned I might die, my mother threw the priest out of the room as the last rites were about to be read over me. Doctors told them that even if I lived, I could be left paralyzed, deaf, blind, or all the above. They were both grateful that the only side effects of my illness seemed to be total blindness with a mild case of neuropathy.

After sharing all that they endured during those four weeks that I was incapacitated, he told me without candy-coating things that he did not raise a quitter. He reminded me that I was a teacher and a principal who expected 100% from all my students and staff. He challenged me to demonstrate to them what 100% effort and dedication looked like. He told me that I needed to be the son he raised and be that man who took life by the horns. I needed to do it as a person who happened to be blind, and I needed to become the best blind person ever.

After that bit of fatherly advice, he said that if I gave up trying to rise above my circumstances, it would destroy my mother. He said he could not let that happen, especially after all we had been through during those long, painful weeks. He told me to curse, punch a pillow, or even break shit, but he was not letting anyone into the room until I got my head out of my ass. He forced me to look at the opportunities ahead for living a full and meaningful life as a person who lost sight but not vision for all things possible.

As I reflect on his life and that time, it was the first time in 42 years that he could not fix what was broken for his first-born son, his “baby boy” –which he called me until he died. But he did remind me that he and my mother instilled in me the tools and fortitude I needed to turn what others saw as a tragedy into an opportunity for exciting new possibilities. Well, I can say here and now that I took those lemons and made a never-ending tall glass of lemonade with a healthy side of Tito’s. That has helped me get by these 17 years after leaving the hospital with my newfound way of seeing and vision for all things possible. That was the single most important thing he could have done for me that day.

But for my dad’s little “pep talk,” my life may have been totally different. I may have allowed myself to become comfortably numb, slip into a life of self-pity, gloom and doom, and give over to depression while I waited for the end of my days. Instead, I took hold of life with a vengeance. I found the strength to stare a few major corporations down for violating the Americans with Disabilities Act and won.

I stood up to a now-defunct international airline for discriminating against my guide dog and me. It was an unfortunate incident, but 40 other passengers stood in solidarity with me and insisted that the airline and its flight attendants on my plane were wrong. They demanded that we all flew home together, or none were getting back on that plane. It was one of the most humbling events of my entire life.

I also got to do a TED talk. I was featured in a film short titled “Albert,” which won the Audience Award at the 2014 Austin Film Festival. I drove in a blindfold taxi derby at the Riverhead Raceway on Long Island. I jumped out of a plane (with a parachute) and started My Blind Spot to ensure that no other person who joined the blind community had to endure the same frustrations I did when thrust into this new life.

Recently, I was humbled to be part of a project, Together We Are Able, which earned two Telly Awards, a Gold for diversity and inclusion and a Silver for social responsibility.

I am not prepared to do what still must be done without my dad here to call and share it with. But with a new day comes new struggles. As painful and new as the loss of our family’s patriarch is, we will move past the pain and the loss, be richer for having had him in our lives, and continually work to do him proud.

For all I know, had he not been the dad I needed at that moment, I may have been stuck wallowing in self-pity and depression, waiting for death to come. Suffice it to say death did come; it just did not come for me. And like Forrest Gump said, “Death is a part of life…”, but I sure wish it wasn’t.

Parents always want to protect their kids. Decades of living with my parents, and counting them amongst my truest friends and confidants, mellowed me to this realization. I am lucky that I had my dad and my mom by my side, even when I did stupid shit to piss them off and disappointed them from time to time. I am honored to call myself his son. Aside from inheriting his dashing good looks and, unfortunately, his Roman nose, I hope I gained his perspective and his level-headedness in moments of chaos.

Since my dad’s passing, I feel more galvanized in paying things forward and making sure to offer fatherly advice to people who need to hear hard truths shared with love and caring. As CEO of My Blind Spot, I’m responsible for telling business, government, and non-profit leaders all the things they don’t want to hear. This usually involves revealing uncomfortable truths that their organizations ignored the needs of their current and potential customers, employees, and other stakeholders with disabilities with the promise of ultimately making things better for people of all abilities.

If I can be half the man my father was and leave the world better than I found it, I can leave this world when my time comes without regrets. Almost 17 years ago, he adeptly assessed the situation in that hospital room and told me in specific terms what I needed to hear, even if I was not prepared to listen to it at that exact time. Had he waited, who knows what life I may have had compared to the rich, fulfilling life I am living today?

Rest in Peace, Pop. I love you and will see you when I see you. Love, your baby boy.